“I’ve been thinking a lot about how time unfolds, how culture unfolds,” said Jeffrey Gibson, in a conversation in the UBS lounge at Art Basel Miami Beach this past December. “We live in a time right now where we can look in retrospect and try to understand how one thing led to the next. But looking into the future, it’s nearly impossible to determine what happens next.”

Behind Gibson, his triptych JUST WHEN YOU LEAST EXPECT IT (2023) could be seen, radiating with electric colors in the otherwise neutral lounge, a chromatic beacon of sorts. The recent work—comprising three acrylic-on-canvas paintings with glass bead adornments—had been commissioned for the UBS Arena in Elmont, New York, but was on view in the ultra-exclusive lounge along with other recent acquisitions to the UBS Art Collection including the works of Nick Cave, Awol Erizku, and Deana Lawson. Gibson’s triptych occupied a central wall in the room, and had a nearly immersive quality, as he’d installed the work on a colorfully patterned wallpaper, Ancestral Superbloom (2023), also of his design.

The installation had a distinctively, and fittingly, celebratory quality, one emphasized by the clinking of glasses and the chatter of collectors buzzing throughout. A few months prior, Gibson had been named the representative of the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale for 2024. A career highlight all its own, Gibson, who is of Choctaw-Cherokee descent, will also become the first Native American artist to do so when the Biennale opens this spring.

For the past decade, Gibson has been based in the Hudson Valley in upstate New York, where he lives with his husband and children, running his studio out of a converted schoolhouse. There Gibson has scaled up the singular and interdisciplinary practice he has been developing for decades, and which merges the traditions and motifs of his Choctaw and Cherokee heritage with the music and pop culture of his youth. His works include boxing bags beaded with indigenous patterns, films, paintings, and a variety of other sculptures. But despite his current successes, Gibson’s journey had not always been straightforward (he even considered giving up his practice around 2010), and he aims to acknowledge that ever-changing relationship to our own pasts and our futures.

“The title of this work—JUST WHEN YOU LEAST EXPECT IT—is an excerpt from the lyrics of ‘Love Comes Quickly’ by the Pet Shop Boys,” Gibson explained. “That song is about love and loving relationships, I wanted to use those words to speak about the times we’re living in and how unpredictable they feel.”

Music, in this work and many works in Gibson’s oeuvre, has been a throughline for reexamining history. “My dad was a civil engineer for the U.S. Army, and I grew up moving around. I lived in Germany, Korea, and the U.K. Music has always been something that I’ve been able to carry with me—it’s grounding. As an American living abroad I was always paying attention to American music too,” he said. In his early teenage years, Gibson began going to dance clubs, and eventually to gay clubs in his twenties, dancing to house music and drum and bass music.

“In my late twenties, I started looking at the lyrics and how they related to the different periods when the music was made, from the civil rights movement to spiritual songs to house music,” he said. “For the LGBTQIA community, during the height of the AIDS crisis, the lyrics of those dance songs are very much about asking for help, asking for attention and acknowledgment. Those lyrics are calls for community. I began to look at these relationships more closely.”

In tandem with music, Gibson also believes that his experiences of living abroad changed his understanding of his American identity. “It’s healthy to be the foreigner,” Gibson remarked. “It’s healthy to not know how to so confidently move around the world but to rely on your hearing or your smell or just kind of trying to decipher things that are different to you. I have always identified as Choctaw and my mother is Cherokee. I was a unique American moving around the world—and though it was never disassociated from being American—it was part of a larger realization about how little people nationally and internationally might know about the Native and Indigenous communities here.”

In recent years, Gibson says he’s felt a lot more freedom with the stories and histories he can explore. “From the beginning of my career, I have been a very process-based abstract painter but I’ve always had actual content that I wanted to discuss, which had to do with Native American materials and history and how it intersected with abstraction,” he said. “But I had to build the context for people to understand what I was doing—with video, performance, sound, painting. Now I’m almost referencing these histories by way of things that I’ve also made over the last 25 years.”

But in the lead-up to Venice, the artist says he is keeping his eye on our own moment rather than the narratives of the past. “Right now, I’m more open to the present of what’s happening—which is complicated and layered. In many ways, our moment is fluid, and while, on the one hand, I feel the urgency of time and time passing, on the other hand, I feel that history shows up in the present. Time extends into this infinite way of looking. We can each set something in motion, but we can’t control how it shows up—whether that’s as an educator, as a parent, or as an artist.”

The spirit of acceptance is leading him in his preparations for the U.S. Pavilion, a process that Gibson describes as unlike anything he’s done before. “There are certainly moments where I am overwhelmed by this opportunity. I kind of can’t believe that it’s happening some days,” he said of the Biennale. “But other days, I know it’s the right time.”

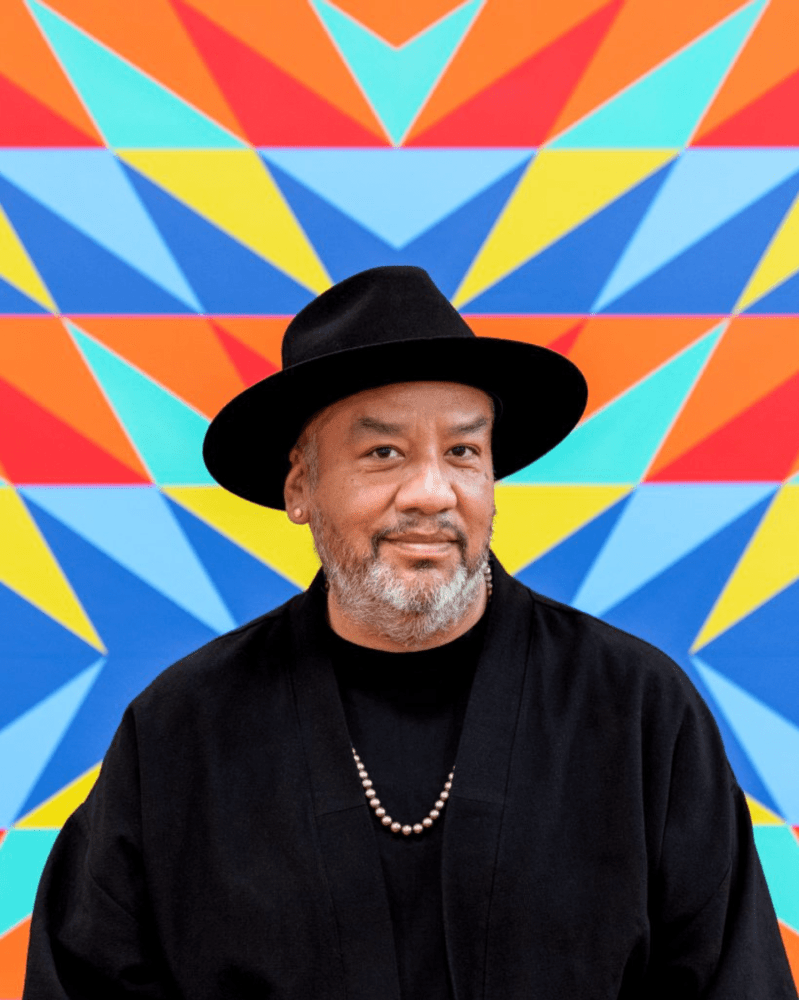

Photo by Brian Barlow.